In Maternal Mental Health Awareness Week, I’m re-posting the 4-part piece I wrote leading up to publication of The Flight of Cornelia Blackwood last year. It’s about my own mental health in the first days and weeks of motherhood, and why I frequently address this topic in my fiction. It’s too long for one post, so I’ve split it into four, and this is the fourth and final post . To read from the start, just scroll down for parts one, two and three.

Moving from psychosis to depression

After breaking down in front of the health visitor, I was diagnosed with PND, but I was still breastfeeding so I didn’t want to take anti-depressants, and by that time, the really scary symptoms had gone anyway. My GP was wonderful, and when I told her how frequently Emma was waking, she said, ‘The first thing we need to do is to get you a good night’s sleep.’ She prescribed something to help Emma sleep for longer. I’m sure this would be frowned upon today, but it was a turning point for me. That night, Emma slept for six hours, and when I woke I leapt out of bed and rushed to her room, convinced she must have died in the night!

When my son James was born two years later, I had a brief resurgence of the PND, and I became paranoid about nuclear war again, but I didn’t have those other symptoms that made me fear I was losing my mind. There are very few photographs of me as a new mother, and I can’t remember why – maybe I just didn’t want to be seen.

One of the very few photos of me as a new mum. This was James’ christening

Post-natal mental health issues are still not talked about enough, and back then they were barely talked about at all, which is probably why I’d never even heard of postpartum psychosis. I was vaguely aware of postnatal depression, but I knew little about it and felt slightly ashamed when I was diagnosed – other women had ‘baby blues‘ and got over it within a few days, so why was I so weak? I was embarrassed. I told no one except my sister and my husband, and ten years later, he tried to use it against me during our divorce, bringing it up as ‘evidence’ that the reason I’d taken the children and left him was that I was ‘mad’ (I left because of his controlling behavior and emotional abuse).

Trying to raise awareness

Much later still, I was happily remarried and making a new life. I trained as a magazine journalist, specialising in health and parenting and contributing regularly to women’s magazines, and the parenting and baby mags. I placed features on many different topics, but I couldn’t get anyone to take a piece on postnatal depression. It was important, I argued, to raise awareness. If new parents and their families recognised the symptoms of PND and the circumstances that might lead to it, there would be more chance of the mums receiving support and treatment.

A common response was, ‘we don’t want to frighten new mums’. I understood that, but it was my contention that if women were more prepared for the possibility that the first weeks of motherhood may not be as joyous as they’d been led to expect, they might actually feel less frightened by and ashamed of what was happening to them. I believed – still believe now – that the enormity of childbirth and the impact of new motherhood is massively underestimated. Not only does your body go through a major trauma, often resulting in minor or even serious injury, but there is also a major emotional upheaval and a dramatic change in lifestyle.

Too tired to smile

Back in the 80s when I gave birth, and even in the early 2000s when I was in magazine journalism, the baby books and magazines didn’t prepare women for any of this. The mum and baby shots you’d find in their pages were likely to make you feel inadequate and guilty. In those first weeks I barely had the energy to shower, let alone do my hair and makeup. The mums and babies in the photos were serene and smiling, but my baby seemed to cry all the time and I was way too tired to smile.

How different are things today?

I often wonder what would have happened if I’d given birth in the age of the Internet and social media. Maybe I would have Googled ‘hallucinations’ or ‘I can’t sleep because I’m scared my baby might die’ and found that I wasn’t the only one. Maybe things would have been easier if I could have chatted online with another mum at four in the morning when my baby wouldn’t stop crying and I was on my knees through lack of sleep. As it was, my best friend, who also had a young baby, lived too far away for me to get to easily. We’d talk on the phone, but during the day when things didn’t seem as bad anyway. Today, I’m guessing I would go on social media in the middle of the night to see who else was up, to compare notes and understand that I wasn’t alone.

Or maybe it would have been just as bad. Maybe Facebook would have shown me even more photos of perfect mothers and smiling babies than the magazines did. I’ve heard so many young mums today saying their friends seem to cope better than they do. Is it more likely to make you feel inadequate if the perfect mums in the photos are your friends? Maybe you’re even less likely to confide in them if they’re regularly posting photographic evidence of their maternal brilliance.

What if, behind those Facebook posts, some of those mums are really crying and desperate but afraid to say so because they think they’re the only ones?

Spread the word!

I truly think we can go some way towards improving the situation for new parents by talking more about the possibility that things won’t be as wonderful as they may have hoped, at least, not for the first few weeks. Both parents may struggle to cope with sleep deprivation and the change in lifestyle. New mothers may even develop a postnatal mental illness which could be mild, moderate, or even severe.

Why is it such a taboo? It’s not as if talking about it will make it happen! It’s so important to recognise the possibility, and if you spot the symptoms, to get help, whether it’s for yourself, or for someone else.

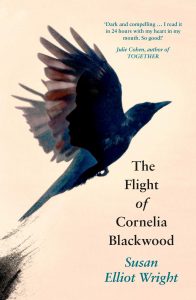

I hope you’ve found these posts interesting and even helpful. I also hope you’ll read my latest novel, The Flight of Cornelia Blackwood which, while inspired and informed by my own experience, is a fictional story about people who never existed. Maybe stories are one more way we can make it easier to talk about these issues.

The Flight of Cornelia Blackwood

To discover more about Postpartum Psychosis and how to get help, contact Action on Postpartum Psychosis (APP)

To learn more about me and my books, please visit my website